On March 18, one month ago, an Uber autonomous vehicle, struck and killed Elaine Herzberg while she was crossing the street. The vehicle did not brake, slow down, honk, swerve or otherwise maneuver to avoid her. It struck her at a full 60km/hr, presumably without ever “seeing” her. The safety driver did not intervene.

Questions Raised about AV Sensing

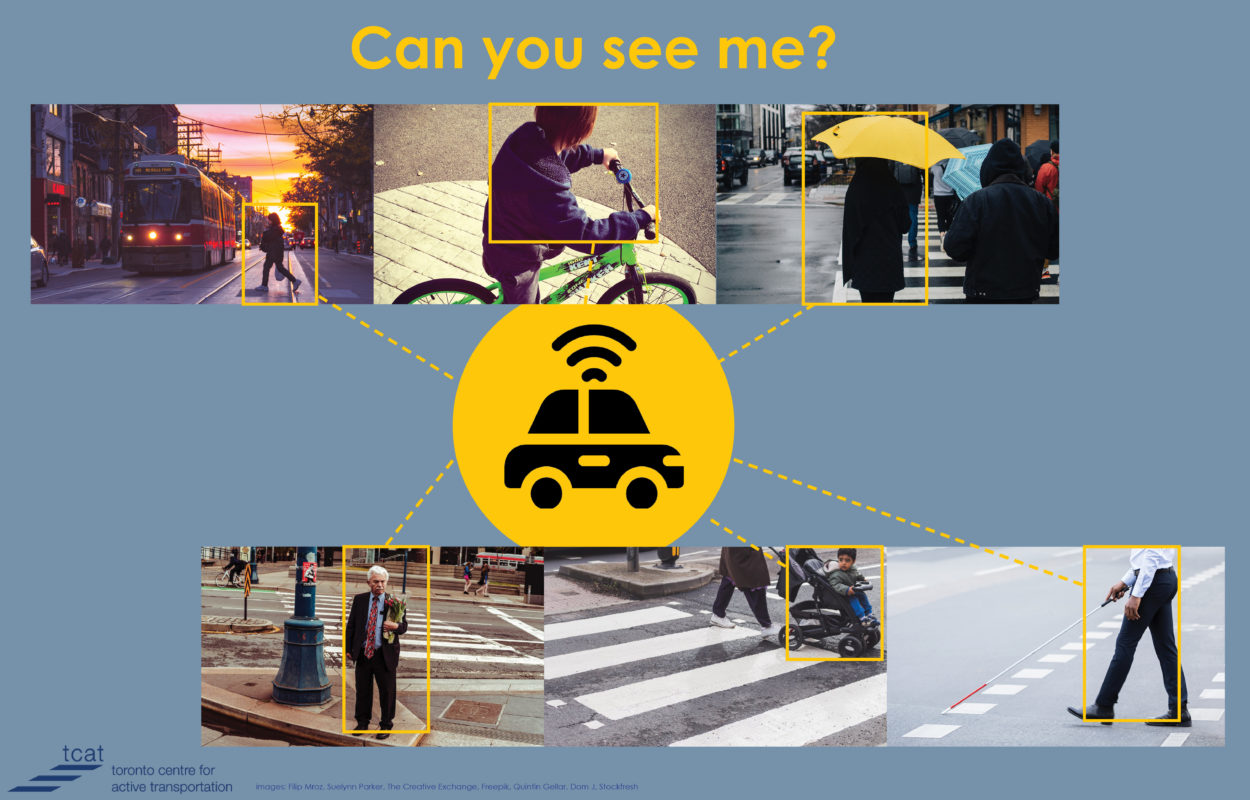

In the wake of this senseless tragedy, many concerns have been raised over the ability of AVs to accurately detect and interpret their environment. How well can AV prototypes actually “see”? What new risks are we being exposed to, by having technology that’s still under development out on our streets?

Currently, a wide range of sensors are used by AVs, such as radar, video cameras, GPS, lidar (like radar but with lasers), ultrasonic and infrared. More sensors are better, but each one costs money. No regulations exist as to what should be included at a minimum. Most, but not all companies, use lidar. Very few companies use infrared, but its heat-sensing capabilities could make pedestrian and cyclist detection more guaranteed.

Even with the best technology, serious challenges exist with ensuring that these sensors work under less-than-optimal conditions. Video cameras struggle to detect center line and lane markings that are worn out (as they are on many roads). Lidar is less effective in rain, snow or dust because of interference from airborne particles. Image recognition is far from perfect – something as simple as a sparkly unicorn sticker can disrupt a vehicle’s ability to recognize a stop sign. These kinds of detection errors can have deadly consequences.

In the case of sensor failure, the safety driver is meant to take over. But this reliance on a human back-up is increasingly being questioned. Is it possible for us to sit alert for hours on end and monitor a system that appears to functioning perfectly well? Testimonials from former safety drivers and reports from the companies themselves point to concentration fatigue issues. The March 23 death of Walter Huang, the second deadly crash of a Tesla on Autopilot, demonstrates again that inattention with our current level of technology is dangerous.

Unsafe Until Proven Otherwise

Following the Uber AV’s killing of Elaine Herzberg, the Association of Pedestrian and Bicycle Professionals (APBP) released a statement calling for the rules of the game to be changed. Currently, legislation requires manufacturers to test AV prototypes before they hit the road, including their ability to sense pedestrians and cyclists, but the tests are designed and carried out by the manufacturers themselves. APBP, along with many other advocates and industry experts, is calling for the federal government or a commissioned third party to create and undertake the tests and publish the results publicly, before an AV is allowed on community streets. It’s important for this regulation to come from the federal level, as there is considerable disincentive for one state to introduce stringent requirements, when in a neighbouring state conditions are lax.

In Ontario, manufacturers who want to test an AV on public streets must sign a declaration that the vehicle is “capable of being driven safely” (HTA Ontario Regulation 306/15 s. 8(1)). At the government’s discretion, they may also be required to demonstrate their vehicle’s safety (HTA Ontario Regulation 306/15 s. 8(2)), but there is no across-the-board, government-designed and publicly reported test.

The Risk of Heightened Responsibility

With AV sensing technology still a work in progress, there’s a real possibility that pedestrians will be asked to pick up the slack to make AVs work. Calls to curb erratic behaviour and enforce stronger rules against people walking are examples of attempts to shift responsibility away from the vehicle operator and onto pedestrians. To assess whether these demands are reasonable, we need to ask ourselves who pedestrians are.

Because there are no tests or exams for walking and a license is not required, pedestrians can have many levels of ability. They could be elderly, and experiencing the lessened hearing, vision and speed of movement that comes with age. They could be young, and still developing their ability to make judgements and assess risk. They could be one of the more than 50,000 Canadians who lose their sight every year. They could have a distorted perception of reality, due to drugs, alcohol or mental illness.

As the city’s ever-increasing pedestrian collisions demonstrate, there is a lot of room to improve on human driving, and eventually AV technology may offer pedestrians a safer street. In the meantime, some tough questions should be asked to ensure that AV prototypes are not putting our most vulnerable road users at risk. AVs need to be able to see those they are intended to protect.